about

• Michael

Klinger • catalogue

• interviews

• documents

• images • Publications • conference

/ events • links

• contact

• home

| |

about

• Michael

Klinger • catalogue

• interviews

• documents

• images • Publications • conference

/ events • links

• contact

• home

|

Interviews |

||

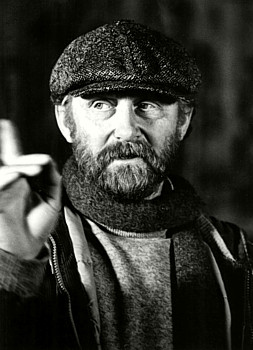

| Mike Hodges This interview with Mike Hodges was by Tony Klinger based on questions suggested by Andrew Spicer. Spicer then e-mailed Hodges with some supplementary questions Questions for Mike Hodges a) Get Carter 1) Were you approached directly by MK about filming Jack’s Return Home? 2) What was the film’s overall budget? Were you involved in the negotiations with MGM (Robert Littman) over the budget or was that all MK? 3) You say in interview with Steven Davies that “a lot of producers have no vision, no idea what they really want”. Did MK have a vision for what became Get Carter? 4) Was MK involved in the screenplay or in any redrafting? How many versions of the screenplay were there? Where are they? 5) Was MK happy with the decision to film in Newcastle (not the novel’s Scunthorpe)? Was MK happy with the use of local stories (the murder of Angus Sibbert)? 6) What was the nature of MK’s role once production was underway? Was he present much during filming? Did he view and comment on the rushes? Did he intervene during post-production? 7) There was pressure form MGM to include more star names/Americans (e.g. Telly Savalas). Was this resisted by MK? Did MK see the film as resonantly British or did he see it as international? 8) Was a sequel or second film about Jack Carter ever discussed with MK? You wrote a synopsis featuring Carter as the possible basis of a film. Was this to be with MK? |

|

|

| b) Pulp 1) Was the idea for a comedy follow-up to Get Carter discussed with MK? Was he involved in pre-production of the script? Do pre-production scripts of the film exist? 2) What was the film’s overall budget? Were you involved in the negotiations with United Artists over the budget or was that all MK? 3) Pulp has an illustrious cast (Mickey Rooney; Lizabeth Scott; Dennis Price) as well as Michael Caine. Did MK negotiate with these stars? Were others considered? 4) What was the nature of MK’s role once production was underway? Was he present much during filming? Did he view and comment on the rushes? Did he intervene during post-production? 5) The “co-operation” you experienced from the volatile Dom Mintoff government in Malta: was that the result of MK’s negotiations? 6) How comfortable was MK with the finished film? He is quoted as saying that it ends “in mid-air” and therefore audiences felt cheated. Did he want a different ending? 7) Pulp performed poorly in America. Was this the result of inept marketing by UA? Was UA unhappy/uneasy about Pulp? Did UA understand what you were attempting in the film? c) The Three Michaels 1) When and why was this company formed? Did each partner have an equal stake/equal control? How was the company to obtain funding? Was UA approached first? Why not a British company (e.g. Rank)? 2) Did it have a particular ethos? 3) Were a number of possible projects discussed? 4) Were any projects developed other than Pulp? 5) Did the company fold after the box-office failure of Pulp? d) General 1) Did you negotiate with MK on any projects after Pulp? Did your relationship continue in any way(s)? 2) What is your overall assessment of MK’s qualities and abilities as a producer? Andrew Spicer; May 2010 Mike Hodges interviewed by Tony Klinger, June 2010) TK How did you first deal with Jack’s Return Home? MH Michael Klinger had seen some of my television work and he’d written to me earlier on saying how much he’d like what he’s seen. And then out of the blue a letter came enclosing Jack’s Return Home and asking if I wanted to write and direct it. And the - the two projects he’d seen on television, Rumour and Suspect, were two ninety minute films which I’d written, directed and produced for Thames Television. So he assumed that I’d want to write the script as well and I did. And I loved the novel, I might add. TK Did you meet Michael Klinger [then] at all? MH No, never did, But he had written to me earlier and there was a mutual friend we had together, Barry Krost, and Barry was my agent and he knew Michael, so I think they were probably talking to each other before I ever met Michael. TK He still manages me, by the way. MH Barry Krost does! You’re the only one, I think. TK He’s doing OK. MH Oh, is he? Good. I’ll talk to you afterwards. TK What was the film’s overall budget? MH I think, I…I mean, one’s memory is a little…[interruption by cameraman because of sirens - omitted] As far as I recollect the film’s budget was 750,000 - and, honestly, I can’t remember whether it was dollars or pounds - I suspect it must have been pounds, which would have been in those days one million dollars, I suppose. TK You were not involved? MH No. I mean, they - obviously Michael and Robert Littman had talked about me and decided that I was the person they wanted to direct the film. Which was quite exceptional, frankly. Because I hadn’t done any feature films at all and Littman was a sort of, you know, high flyer at MGM in those days. TK You say in an interview with Stephen Davis that ‘a lot of producers have no vision, no idea of what they really want’. Did Michael have a vision for what became Get Carter? MH Well, I think Michael’s genius was - well, I say this, this doesn’t sound very humble - his genius was to look for a director he actually wanted to work with. So he was the first person to choose Roman Polanski’s first two English-speaking features, prior to me, that was. He always referred to me as ‘the ginger-haired Polanski’. But, in between, he’d had Peter Collinson, and there was another, very good director … TK Alistair Reid? MH Alistair Reid. And so his genius was to look out for good directors and then let them get on with it. I mean, he was wonderful in that respect. Both the films that I made for him were completely at my own discretion in terms of how they were made. Obviously, I collaborated with him in terms of casting and he would contribute, I mean, he contributed Sir Roy Budd in terms of suggesting him to do the music for Get Carter - that was a mighty big plus. TK Was Michael involved in the screenplay or redrafting? MH It’s a long time ago, but I remember - what’s extraordinary about Carter, I can hardly believe it frankly, that I’ve got the letter in January of 1970 and the next letter when I looked in my files was from Robert Littman in October of the same year saying how terrific he thought the film was. I mean, this would be inconceivable, that you could move from, at that pace, to get a film finished. It does say a lot about Michael Klinger as a producer that he was able to pull that off. In terms of the script, I’d never adapted, both the works that I’d done earlier were my own original screenplays. So - initially I found it difficult to adapt Ted Lewis’s novel to the screen. And I kept very closely to the structure of the novel. Then I decided - because the novel is actually a flashback, basically - and I decided that I didn’t think I was either skilful enough or whether the film didn’t actually need it. So I decided on another structure. But I don’t recollect ever having any problems with whatever suggestions Michael made - I listened to and we came to a compromise and so on of the script. TK How many versions - were there more than one version of the script? MH I did a first draft where I stuck pretty well to the novel as it was. I’m not sure I ever showed it to anybody. I had to go through that process to eliminate it. And I had to go through that process again with my third film which was another adaptation of a novel by Michael… Coutts? Oh, who’s responsible for ER? TK Michael Crichton. MH Michael Crichton. So, I’ll start again on that one. About a year later I again found myself adapting a novel by Michael Crichton this time called The Terminal Man. And by this time I’d realised from the experience of doing Get Carter that you had to break, in a way, from your responsibility to the author in a way. That you can be just a little too careful and you have got to think of it as a film and not a novel. So I moved quite rapidly to the point where I felt I had to shift into - shift the novel into a film script and make it much more of a film. TK Where are the other versions? [laughs] It’s a research question. Are there any other versions of the script? MH [Laughing] You know enough about film making to know there couldn’t have been time for any other versions. TK I was telling someone the story the other day, the timescale from that phone call to it - to Barry Krost after seeing Rumours … MH Rumour, yes … TK From that phone call to it being in a cinema somewhere, a screening, was 37 weeks. It was ridiculous. MH Of course, I thought it was going to be like that all the time. Was I wrong! [Laughs.] TK I still make that mistake. It would be nice. Was Michael happy with the decision to film in Newcastle as the novel’s originally Scunthorpe? MH Well, the novel wasn’t set anywhere, in truth. In the novel Jack Carter changes the train at Doncaster and you never know quite where he ends up. It’s obviously a steel town, I would have thought. At the end of the novel he’s perched on the - on a - what do they call those things where they … a brick foundry or something like that. Anyway, whatever, one of the reasons I wanted to do it was because I’d done my National Service not all that long before, about 10 years before, and I ended up in the Royal Navy. And I’d then been attached to a minesweeper and I was also an ordinary seaman, so I was not officer class and I was - the minesweeper was attached to the Fishing Protection Squadron. So, as a consequence of being in this lowly position, I found myself in all of these unbelievable fishing ports right the way up … round the United Kingdom, right the way round the UK, Iceland, Norway, all these places. And I saw how the horrors basically of all these towns were. I couldn’t help but connect the novel and a lot of locations in the novel, particularly the pubs and the various places I’d seen and these Hogarthian places that I’d visited. Like in Hull there was a pub called ‘The Albert Hall’ and it was as big as the Albert Hall. And this is in the Fifties, of course, in the late Fifties. And the fishermen would go in there and they had unbelievably hard lives, and their wives, and there was a lot of drunkenness, just deep sadness, actually, in the place and extreme poverty. And I couldn’t help but connect all of these places to the locations. So in a way this was the biggest step that I made in terms of taking the novel and making it into my own film as opposed to a literary work. And I started associating all these places that I’d actually seen to the scenes set in the film. So Michael got his trusted cadillac out and his trusted driver Reg Nibbit and off we went, to my embarrassment, because this large, opulent car going to all these poverty-stricken places was slightly embarrassing, but anyway, there we are. So we went up the East Coast, because I was convinced we were going to get … [interruption by film crew - omitted.] Right, so he got the Cadillac out and we went up the East Coast because I was convinced that either Grimsby or Lowestoft or Hull or wherever were going to be wonderful locations. Also we’d have the sea, it would free it up a little bit more. But what had happened in the ten years since I’d been to these places, they’d really become gentrified. They’d been rebuilt, ‘The Albert Hall’ had vanished in Hull and so on. So we went further and further up North and I was getting very depressed because I didn’t see any of these places as suitable locations. Now, I’d been - sailed into North Shields, I’d come in by sea and now, coming back by Cadillac, we had to get to North Shields which I still remembered as being one of the most extraordinary places I’d ever been to in the Fifties. I mean, by the fish jetty there was an area round the back known as ‘the Jungle’, this was in the Fifties, and the local rackets were run by a guy called Addo who was a black man which was incredibly unusual in those days. And the area was terribly poverty-stricken, but it was also wonderfully dramatic because of the ferry going across and so on. So, I’m trying to get to North Shields and stumbled across Newcastle as we are now coming by land. And as soon as I saw Newcastle I realised that this is where we should shoot the film. I mean, it had all the hardness of Jack himself. You could understand how someone like Jack Carter could actually emerge from a place like Newcastle. I’m not being rude to the people of Newcastle but it was a tough city and Jack Carter was a tough man. So visually it said immediately what it should be. And Michael was perfectly happy with that and he in fact returned to with the Cadillac and Reg and left me in Newcastle where I now lived for about two or three weeks and went round all the area and found these locations which I eventually used in the film. And I adapted the script that I’d written to Newcastle and what I’d found there. TK A question as a director. Was there ever a time when you thought, ‘I’m going to have Michael Caine, it’s in Newcastle, I want Michael to do a Geordie accent? MH No, never thought that. I did with the other cast. I thought I’d have to make the leap that Carter had been out of Newcastle for a long time and had been mixing with London villains and he would have adopted their, a slight brush of their accents. No, I didn’t. TK How does - research has shown and has thrown up that you used local stories in the script, including the murder of Angus Sibbert. MH That’s right. TK How did that happen? MH Well, because my background really was documentary. I’d worked on World in Action so consequently every film that I’d made so far was based on very hard research. And although I wasn’t trained as a journalist I sort of acquired it through working in television. So whilst … when Michael and Reg left me in Newcastle to sort of explore the area, I then remembered that there had been a murder at a place laughingly called ‘La Dolce Vita’ which was, I mean, ironic in terms of setting a nightclub with a name like that in a place like Newcastle which was a very deprived area. And I stumbled upon, basically, the story of Jack Carter, or ‘Jack’s Return Home’ as it was called then. And a hitman has in fact been sent up to…er…to eliminate someone who’d had their fingers in one of the local villain’s pockets. So I was able really to use that and to sort of embed it in the script as I’d written it and Ted Lewis’s story.[Interruption in which TK tells the story of how he went to Czechoslovakia in the Cadillac with his father during the Russian invasion - omitted.] TK What was the nature of Michael’s role once production was underway? MH Well, his … he was extraordinary in terms of providing me with … I must have driven him mad on occasions, but he’d provided me with everything I wanted. He was one hundred per cent behind me, I mean, on both films that I made with him and I’m sure it was with other directors as well. So his role was to protect me and to give me everything I needed. TK Was he present much during the filming? MH Yes, he was there quite a lot. He was up in Newcastle the whole time, I think. I think so. TK He was, yes. I just wondered how much you were aware of him being there. MH Oh, yes. Richard Lester had said something to me before I started. He’d suggested I stayed in a different hotel to everybody else. So I did. It was a wise suggestion because I stayed in another hotel - it wasn’t far from where the crew and Michael and everyone was based. I was with just my first assistant director. Because what happens is that when you are doing a feature film, especially when you are on location, you enter the foyer and it’s just like being attacked by piranha fish, everyone wants answers. So I protected myself by staying somewhere else. It was very good advice, I thought. So whilst Michael was there, he wasn’t breathing down my neck. So that when I finished at the end of the day, as long as I was on time and on schedule and there were no problems, I could have my own life and I could restore my energy levels and I’d be ready to go the following day. TK The piranhas must have descended on him! MH Exactly. So that’s one of his functions. I don’t remember him being any thinner at the end of it, I must say. [Laughs.] TK Did he view or comment on any of the rushes, the dailies? MH Well, we all saw the dailies, I mean, so, I don’t know, they were all so positive and so good that I, that everyone was so terribly excited about everything that was going on. Another thing that Michael did was that he actually suggested that I used John … TK John [mentions inaudible surname]. MH No, no, no, John … TK John Trumper. MH Yes, he suggested that I used John Trumper, who was a brilliant editor - irritating person, but a brilliant, brilliant editor, and I’ve always been very grateful to him for what he … how much he contributed. We fought like cat and … nine tails the whole way through, but he was a very good editor and Michael suggested him for that role too. So, in terms of the rushes, we all saw them. Michael Caine, I don’t think. He didn’t like watching his own rushes. So, you know, Wolfgang Suchitzsky, who was one of my contributions was doing such a good job and I had my own operator I’d made my previous film with, Rumour, you know, I had Dusty Miller, and so I had a very good team around me and the rushes were just very good. TK Did Michael intervene at all, or did he have to intervene, during post-production, or did he get involved? MH No, again, well, he was there a lot, but in terms of the dubbing and the music he was in and out like producers are, but, again, it was left to me. I had another contribution I made because I had this wonderful sound editor, Jim Atkinson, and I think Jim was so wonderful because he would give me so many different options. He was so obsessive about the job, but I think Michael found him somewhat irritating [laughs] because he thought I was being offered too many options, I think, probably that it might confuse my poor little mind. But it wasn’t. Jim and I got on incredibly well. TK There was pressure, and I remember some of this, from MGM, to include some more American star names. MH Yes … TK I think Telly Savalas was one, I think I remember Edward G. Robinson was one. MH Oh, right. [Laughs.] Well, the casting of the film was completely daft, I have to say. My previous films on which I got the job, basically, no one even asked me who was in the cast. So, you know, this is in the late Sixties, in television, and the star process, in a sense, had still not seeped into the very depths of television, so you were just left to cast the right actor. When I did, worked with Michael on Get Carter, I assumed when I got, when Michael Caine came on board, that was that. I didn’t think I’d have to start casting every person as a star, which is now customary. And … but MGM had other ideas and they wanted a lot of these other characters, the villains etc, to be named American, often American, actors. And I don’t know how many times I threatened my resignation but I just fought tooth and nail. I had a wonderful casting lady, Michael introduced me to called Irene Lamb, and I just fought to have the other actors, and I won pretty well them all, who had never been on film at all. So it gave Carter and Michael Caine’s performance, a kind of reality, which I think would have been lacking if you’re sitting there star-studying - star-spotting. TK Did Michael back you in that fight? MH Michael - yes, he backed me. You know, Michael was, I mean, I think his commercial instincts would undoubtedly have said, ‘Yes, I’d like a few more stars in there’, and also he’s got to appease MGM, so his position was slightly difficult. I never asked him but I suspect that he was terribly grateful that I was so adamant that I would not have these people in the film. TK Did you, and he, see the film as being resolutely British, or did you, was it international? MH Oh, absolutely, I … [hesitates] I’m sure we thought of it as British, I don’t think … Of course, you must understand that the British film industry was in a slightly different state, then, actually. That there were a lot of British films which were successful, you know. We had Woodfall Films, you had Richardson, you had Lindsay Anderson, you had a range of directors who were making very good British films who were commercially viable. TK Was a sequel, a second film about Jack Carter, ever discussed with Michael? MH No. I killed him in the end, you see. That was not in the novel. Well, the novel, you’re not quite sure whether he is going to die or not. The implication is he is going to die. There was never any kind of discussion because I really felt quite strongly that he should die at the end, that he should be dismissed in exactly the same way as he’d dismissed all the other people. TK That’s how I remember it, but I have from research by other people that you wrote a synopsis featuring Carter as a possible basis for a film. MH Ah, that was many, many years later, and I was … it was a prequel, actually, because, oh, it was actually, I worked on the premise that the character of Britt Ekland, who was this gangster’s moll, so to speak, and Carter were having an affair which was, in a sense, in the film played down slightly. They’d had a child after he’d been, after his demise, and the child had been adopted, and it was the confusion of the parents as to having this completely psychotic young man and how he’d found out eventually who his own father was. But it was never entertained by anybody, actually. TK But that was nothing to do with Michael? MH No, no. It was… and Michael was dead, I think, already. This was some years later. TK OK. I’ve got some more Get Carter questions and I’ll [inaudible]. MH Right. TK Do you think Michael’s background as a distributor might have assisted with the qualities he brought to the film, or films, such as Get Carter? [Interruption for aeroplane. Tony repeats question.] MH I would say that his prowess as a distributor affected incredibly the way that Carter was publicized. I mean, it was a brilliantly advertised film. I mean, the promotion was extraordinary. Every single bus in London had ‘Caine is Carter’. It was the first time I think, those little blocked images on the back of London buses. And the posters, which are now, you know, extremely valuable, of course. So the whole of the distribution of the film in the UK, I have to say, was excellent. But, sadly, it was not the same with the MGM end in America. But still, it survived over there. But they were going through problems which seemed the bane of my life, quite frankly, pretty well all my films seem to end up with companies with problems. They put it out as a drive in, but it still survived. Of course, a year after in America they made a black exploitation replica of it, basically. I always suggested they should have just run the negative, actually [laughs]. TK Michael was celebrated for bringing many European talents to Eur … er, to the public attention. MH Yes. TK Do you think of films, this film, as being one of them, being a British film obviously, do you think it also showed a European sensibility with that material, or do you think it was just another British film? MH No, I - he was very European, I think. He changed, I think he had to. Because at the time, again, the British film industry and the European - because you have to remember it was during the whole of the French sort of Renaissance, with New Wave films and so on. So European films were very important and vital and at that time he was certainly, in this country, was at the hub of it. He was it, actually, in many ways. TK Do you think Michael’s films pioneered a link between quality films and pulp formats in that era? MH [Hesitates.] Well, they were all very…I mean, they were all very classy pulp films, if that’s the word. I’m not sure I would say they were pulp films. They were horror films and certainly he and Tony Tenser - that was the area they explored, wasn’t it, to a large degree? TK To the point of the break-up of the partnership, that was the point at which Michael [inaudible]. MH That’s right, yes, so he wanted to move off and do other … I mean, the two films he made with Polanski were absolutely extraordinary and very brave films to make. TK Extraordinary films. MH Absolutely. And I think that says a lot about him - that he had some instinct to … to actually move towards the art cinema in many ways, but still concentrate on good storytelling. TK It was too much reading Dostoevsky and Tolstoy as a boy. MH Did he really? I didn’t know about that. TK Yes. Do you think Michael’s films as a producer managed to reflect the wider social concerns in 1970s Britain? MH Do I think what? TK That his films - the films that he produced - managed to reflect the wider social concern that was prevalent in 70s Britain. MH I don’t see - Carter sort of indirectly, certainly, but I don’t know that any of the other films were his main concern. I mean, he kept his eye firmly on entertainment, quite rightly, in my opinion, and, in terms of the social concerns, he was himself a socialist and Labour Party supporter, we both were. I think that just comes out in your films if you are of that inclination. Then it’ll emerge, but it’s in the details. I wouldn’t say he was a great proselytizer in terms of his output. TK How would you view Get Carter - as a crime film, a realist drama, or both? MH I would say both, actually. I mean, I think it’s a…you know, I mean, it’s, it’s…it has a kind of classical theme, actually. It’s almost like a Greek tragedy. It’s also like a Western. I mean, I never thought of it, when I was doing it, but the influences of the Western and probably Sergio Leone, of that kind of film-making, er, comes out in Carter. Almost, the use of space. I mean, there’s something very odd about British films [interruption because of noise]. TK Why do you think Get Carter remains such an influential movie? MH Oh, lordy. I’m not very good at answering questions like why is Get Carter such an influential movie. Er, I don’t think I can answer it, to be truthful. Somebody else could answer it, but I can’t. TK That’s a good answer. MH [Laughs.] TK Was it your intention to make such an explicit comment about real life crime and local government corruption? MH Yep, I mean, I [laughs], I’ve always found the United Kingdom a really deeply hypocritical place. And when I worked on World in Action in the Sixties it took me all round not only the UK but America, Vietnam and I dealt with a lot of politicians and I saw how the system worked. It was very patently obvious. I … by the time I got to make Get Carter, I was pretty aware what was going on, you could sort of smell corruption and the UK was full of it, as indeed was the UK police force. Everyone in those days said, ‘What a wonderful country. It was Johnny Foreigner who was corrupt and the foreign police were corrupt and so on, not the British, and the British Bobby was perfect and so on and so on. It was patently obvious to me that this was not the case and in Newcastle you could actually feel it in the air. And, erm, of course, subsequently it was all, it all came out and it was a highly corrupted city - and the council and everything. And now, of course, we realise that the whole country’s actually corrupted now. So, yes, it was definitely part of my intention. TK Perhaps it’s time to make another one. MH Yes [laughs.] Except everyone knows it and in those days they didn’t. TK Er … I don’t like the next few questions. MH Don’t worry. TK Moving on to Pulp, let’s move on to Pulp. MH Oh, yes, right. TK I think we’ve done Get Carter - to death. Was the idea for a comedy-type follow-up to Get Carter discussed with Michael? MH Well, Michael…we wanted to make another film together for obvious reasons, apart from the fact that I needed to earn more money, and … because I didn’t get paid very much for Get Carter. I got £7,000 for writing and directing it, which is fine. I’m not bitching about it, but I thought the next one I did with Michael maybe I should get a little bit more. And …er…but, anyway, so we decided…cut all of that, it’s not relevant. Well, Michael wanted to make another film with me and I was anxious to get back to my own original screenplays. So, he came to me with various projects which I didn’t fancy which were scripts already written and so on. So I said I’d like to try and write something for him and Michael Caine again as we’d been so successful and it was a very happy partnership. And I, I wouldn’t accept a commission from them, I wanted to write something on spec. and see if they liked it and wanted to make it and we could raise the money then we’ll do that. So I spent six months writing the script for Pulp - which is a hard script to write, I found it terribly difficult, although it was something that I passionately wanted to do. And Michael read it - both Michaels read it - and we made Three Michaels. We had The Three Michaels and United Artists put the money up and we went ahead and made it. And, again, it was very straightforward actually. TK Was he involved in pre-production of the script, Michael? Or was it, I mean - at what point did Michael get involved with it? MH Michael got involved, I was writing it for him, both Michaels, in fact. And he did, because it was going to be shot in Italy initially, he did arrange for, the only finance he had to put in to it was for me to have a trip to Italy. And I went to Naples, all round Italy, looking for locations. And eventually … but, actually, by that time the script had already been written. I’m sorry, I’ve got it the wrong way round. So, when they read the script and liked it, then he’d let me go to Italy and I spent two or three weeks and I literally went from top to bottom of Italy looking for locations. And I, basically, we were lined up to shoot, we had Michael Caine and the cast was being put together. And another great moment in my career with Michael was the fact that working in Italy, researching in Italy for locations, I realised that we were going to be taken to the cleaners. I mean, every city that I’d suggest we shot in we had to do a deal with the Mafia. In addition to which, the locations were going to be split up. And by this time I was smart enough to realise that ideally you keep all the locations as close together as possible. Like in Newcastle, you, literally, you know, every location apart from the house at the end of the film was all within sort of fifteen or twenty minutes of where we were all staying. So I literally, four or five weeks before we started shooting, I rang Michael and I said, ‘Look, I think it’s dangerous for us to shoot in Italy. We’re going to be taken to the cleaners for all sorts of reasons.’ And I suggested that we shot in Malta which was a small island that I knew. I had a house there. And I knew that I could probably find all the locations there. And, although it wasn’t in Italy, it would be just as good. And to this day, I can never believe that he actually said, ‘Yes’. And, you know, we were four or five weeks off shooting. This was a massive shift. And he was wonderful like that. I mean, it was a hell of a brave thing to do. Most producers, I think, would have shied away from it, frankly. Though he was smart enough to realise the fact that it was a sensible suggestion. TK Yes he was. I think he was terrified of the Italian Mafia. MH I think he was quite right to be. TK What was the film’s overall budget? MH Pulp, again, it wasn’t very expensive. I think, in dollars, it was one and a half million, something like that. I would have thought dollars. Or maybe it was just a million dollars, I don’t really remember. TK Were you involved in negotiations about the budget with United Artists or was that all Michael? MH No, all Michael. Michael and I, I don’t, you know, we never discussed budget, he just took care of that. TK In the casting, as well as Michael Caine, you had Mickey Rooney, Lizabeth Scott, Dennis Price. Who came up with those? Was that casting or was it your idea or Michael’s? Who came up with those? MH Well, the role of Mickey Rooney - was the sort of cross between James Cagney and - who’s the guy who tossed the? - George Raft - and the whole point of the character was that he was this tough guy, but he was tiny. And United Artists, I kept wondering if they’d ever read the script, because the script is all about this small, little man, you know. And they were suggesting all these insane, huge, and I’m talking physically huge, actors to play it. And I would say, ‘Please read the script,’ and they were terribly reluctant to have Mickey Rooney. Mickey Rooney at that joint in time, you know, he was a faded star. And, of course, he was absolutely perfect for the role. Then, Lizabeth Scott was certainly one of my favourite actresses [interruption for background noise]Lizabeth Scott was one of my favourite actresses and the whole film was a sort of parody of…I mean, I was terribly influenced by a John Huston film called Beat the Devil, I have to confess. Beat the Devil was not a successful film. I loved it. I thought it was just absolutely wonderful. It had Humphrey Bogart and Gina Lollabrigida and so I…and Truman Capote wrote it and so on and so on. So there was - it was the antithesis of Get Carter, yet it was very similar to - in terms of its structure. It was about a girl being abused etc. etc., the corruption, although this was much more political corruption. And what motivated me was, basically, that in Italy just before I started writing it the elections had happened and, to my utter astonishment, the Fascists were back. I’d assumed as a young man when I’d witnessed the horrors of the Holocaust in World War Two that Fascism, no one would contemplate Fascism again. Naïve of me, of course, but that’s the process of growing up, and I realised that there was this big swing in Italy, but that was one thing. Then I based it on a scandal that had happened in the Sixties called the Montesi scandal when this young girl’s body was found on a beach and the Italian press and the whole media and the police and everyone - it escalated. Over ten years it went on while they were trying to find out who did it. There were court cases. It was hysterically funny. Everyone became involved, it was a bit like the Profumo scandal, the equivalent here, where everyone’s names were being bandied about and everyone’s names were in the pot. And then with the Montesi scandal it was the same. So my comedy was based on that, but it was basically a political comedy, I mean. TK What was the nature if Michael’s role in the production? Was it the same as in Get Carter? MH Very much the same, you know. And, I mean he let me - the script was totally my own and totally original. And he was just one hundred per cent behind it. I mean, he told me afterwards, many years later, that he loved the film most of all his films, actually, which was rather charming of him, I must say. TK He absolutely believed that. MH Yes he did. He loved that film. TK Dad had a very good relationship with Dom Mintoff. How did that come about? MH Well, Mintoff, of course, was a socialist as well. And, I mean [interruption for background noise] Well, this is perfect, don’t you think, Especially as we’ve just mentioned Dom Mintoff and all the sirens have started going off. So, I mean, I was so busy, actually, making the film, but I think it was something to do with … we wanted a funeral carriage. There was this amazing funeral carriage. And they were trying to charge us a ludicrous sum of money. It was the only one on the island, you know. So I think Michael was so outraged by this that he somehow got to Mintoff and they became great buddies. And they were both socialists and Michael was, you know, sort of, I wish he was alive still, I could ask him a lot more questions than I did. But I’m not sure where he stood in terms of the monarchy or anything like that. He probably was a Republican, I would have thought, at heart. But he and Mintoff hit it off and I think they used to go swimming together - with, you know, and the British, a lot of the British and the Europeans living in Malta hated Mintoff. But Michael got on very well with him. TK He did actually mediate between the two countries at one time. MH Did he? No, I believe you. TK Yes. How comfortable was Michael with the finished film. There is a quote apparently which says he felt the film ‘ended in mid air’. MH Was this Michael? TK Michael Klinger. I never heard him say that myself. MH Well, in a sense he’s sort of right. [Hesitates.] I mean, the story is going to carry on. But there was nowhere else to go at the end. I think the ending is rather wonderful but it is … he is in the air. I mean, that’s the nature of that particular beast, I’m afraid. TK Pulp didn’t do well in America, particularly. Was this the result of inept marketing by United Artists? MH Hopeless, absolutely hopeless marketing. I mean, there’s a quote that’s always repeated on W. C. Fields’ grave, ‘Rather here than in Philadelphia’. I think they opened in Philadelphia with the red carpet treatment. But what happened with Pulp is rather wonderful. They opened with the red carpet or whatever and it was a complete failure. And there was a new cinema, shortly afterwards, opened in New York. And they dedicated the cinema to lost films, basically. And the first film that they ever showed was Pulp. And it was not long after it had failed at the box office. And it got these rave reviews, really, on television, everywhere. But the reviews came out and the film was only running there for a week, So, by the time the reviews came out the film had closed. So they were now, I mean, you’re talking Time magazine, everything, with these great reviews. So they then had to run around and try and find a cinema. I mean, it sort of survived there, but it was a complete hash, complete hash. I’m going to sneeze, excuse me. TK I remember it being in the top ten films in several lists. MH Absolutely. No, no, it was very well received. TK It’s very annoying. It was actually my favourite film of my father’s. I couldn’t believe that it was a failure. Do you think United Artists had any idea of what you were attempting to do? MH No, none. I - when I was saying about Mickey Rooney and they hadn’t read, seemed not to have read the script, the…one actor - who played Hercules in Unchained and …? TK Steve Reeves. MH No, no, no. There’s somebody else, another big star. Big. I know. So - they didn’t understand it - I should have realised right from the beginning, because with the Mickey Rooney character, who had to be small because the script says, one of the people they kept suggesting because he’d just made a comedy which apparently was rather good - and he’s a terrible actor normally - was Victor Mature. And I said, ‘Victor Mature? This is insane!’ [Laughs.] So, of course, I should have known then that they didn’t understand the film therefore, had no idea what they were doing, really, no idea. TK [Indistinct] I never knew Victor Mature was … MH So, there’s another story. George Martin, of Beatles fame, did the music. And George and I had a lovely time together. And he wrote this tune and he suggested I wrote some lyrics. And he was a big figure in the music market, right? So I wrote the lyrics for one of his tunes which was called ‘Pulp’ and we were going to get Sacha Distel to record it because he had a connection with him. I went to see the music department at United Artists with the lyrics. George wasn’t with me. So the guy reads them and says, ‘Who are you?’ to me, for a start. So I said, ‘I wrote and directed this film’. And he said, ‘You didn’t come up with the fucking title, did you? Who came up with that title?’ I never heard another word from them, that was that. So they had no idea. TK That is unbelievable. Going on to The Three Michaels, when…er…did each partner have an equal stake, equal control? MH We all had the same front fee and then obviously Michael, the two other Michaels, not me, had bigger percentages than I did. TK And how was the company to obtain funding? MH How was …? TK The company to obtain funding? [Interruption while Mike Hodges is offered something to blow his nose and declines.] MH Well, it was only set up to make one film I think initially - so United Artists. TK Was a British company ever approached to fund the film? MH I honestly don’t know. TK I have a feeling Rank might have been. MH Rank? Oh, yes, I’ve sort of got the feeling Rank might have been … TK I’m not sure. MH No, no, I’ve got a feeling Rank may have been. TK Er - were any other projects discussed for that company? MH None, none. I don’t think Michael Caine enjoyed making it very much. He didn’t like Malta at all and he was going through some quite difficult domestic things. So I think sort of the love was slightly tainted at that point. TK Interestingly, when he produced that film with Frederick Forsyth several years later, when he actually physically got involved … MH Who, Caine? TK Yeah. MH Right. TK He had one other attempt at producing and hated it, apparently [rest indistinct]. Did you negotiate with Michael over any other projects after Pulp? MH We flirted with each other on a script called The Chilian Club and I wrote a script and we had a falling out, actually. And I went through a very difficult period after The Terminal Man in terms of I was trying to set up a film and I’m not good at it and I took four years out of my life and Malcolm McDowell was going to be involved. I’d written a script and so on and so on. And I needed another film. Anyway, I’d written the script for The Chilian Club but then I was asked to do Omen II which was a fairly disastrous decision on my part. Having been asked to make Omen I which I’d found the script to be absolutely ludicrous, but, in fact, I thought Dick Donner did a very good job making a very good film. But from very unpromising material, to tell the truth. But, anyway, part II, the political story in it appealed to me. Anyway, so I suddenly decided I’d do it. And I think Michael was very upset because I think he thought I was going to make The Chilian Club next or whatever. Anyway, we had a short spat which we resolved eventually. TK So your relationship continued to be a friendly one? MH Oh, yes, no, it absolutely did. But then he also asked me to do the first one, was it Gold, the first one? But I wasn’t drawn to the South African adventures particularly, it wasn’t my cup of tea at all. TK I think we should stop there. MH Exactly. No, I don’t think there’s anything else. Follow-up questions for Mike Hodges Get Carter 1) You say that you were under pressure to have American stars in Get Carter. How far was MK swayed by this view? Did he have any suggestions about who those stars might be? (Telly Savalas?) 2) You say in your interview with Tony K that, before committing to Pulp, ‘Michael Klinger came to me with various projects’. Can you give some more details about what those were? Was one of them a Wilbur Smith adaptation? Was one of them an adaptation of Laurence Henderson’s Cage until Tame published in 1972 - another gritty, revenge-based crime novel and a possible follow-up to Get Carter? I found a copy in the archive and noticed that there was a note renaming the novel Jack Carter - Cage until Tame. Were you offered any other crime novels to adapt? Were you involved, at this point or later, in MK’s plans for a possible Get Carter television series? Why didn’t you find MK’s choice of material attractive/interesting? Pulp 3) You describe the writing of Pulp as ‘very difficult’. Why was this? 4) Why was Pulp ‘something that [you] passionately wanted to do’? 5) A minor point: but why were you so insistent in obtaining the Magritte paintings for the film? This was a difficult and expensive business! The Three Michaels 6) Was this company set up solely to make Pulp (or what became Pulp)? Were there any further plans to make other films? Were there differences in the way that the participants viewed the company? Would it have continued if Pulp had been more commercially successful? The Chilian Club 7) Your script is a very loose adaptation of the original. What was your attitude to George Shipway’s novel? What was its attraction for M K, another socialist? Did you collaborate directly in the re-writing with Benny Green and MK? General 8) You seem very wary of ‘South African adventures’ and turned down the opportunity to direct Gold. What created this scepticism/uneasiness? Michael Klinger as producer 9) You praise MK for his faith in young directors and in finding directors with whom he wanted to work. What would you say were the other qualities that made him stand out as a producer or that made him stimulating to work for? Was MK a good judge of scripts? Did he comment perceptively on rushes and suggest retakes or alterations or did he leave that to the director? Did he ‘interfere’?! Were there ‘creative differences’ in the making of Get Carter or Pulp? Did Klinger’s approach to production differ from his contemporaries? (e.g. Dino de Laurentiis). 10) What would you say was MK’s contribution to British cinema? Get Carter Q You say that you were under pressure to have American stars in Get Carter. How far was MK swayed by this view? Did he have any suggestions about who those stars might be? (Telly Savalas?) A All producers want as many stars in their films as they can get. Telly Savalas was one, I seem to remember. Also the Canadian lead actress in tv’s Peyton Place and Joan Collins another. Q You say in your interview with Tony K that, before committing to Pulp, ‘Michael Klinger came to me with various projects’. Can you give some more details about what those were? A I think one was called “Limey” - not the one subsequently made by Soderbergh. It was for Caine - but I still didn’t want to make it. Nor did Caine when Michael changed the main character’s name to Michael Mickelwhite. Caine was not amused. Q Was one of them a Wilbur Smith adaptation? A Michael offered me “Gold” - but when, I know not.Q Was one of them an adaptation of Laurence Henderson’s Cage until Tame published in 1972 - another gritty, revenge-based crime novel and a possible follow-up to Get Carter? I found a copy in the archive and noticed that there was a note renaming the novel Jack Carter - Cage until Tame. Q Were you offered any other crime novels to adapt? Were you involved, at this point or later, in MK’s plans for a possible Get Carter television series? A No to all the above. Q Why didn’t you find MK’s choice of material attractive/interesting? A Not so. He asked me to write and direct a film based on “The State of Denmark” by Robin Cook. I was very excited by the project but he couldn’t get it financed. Pulp Q You describe the writing of Pulp as ‘very difficult’. Why was this? A Because I was trying something new (for me) - a black comedy that was also political! Q Why was Pulp ‘something that [you] passionately wanted to do’? A See 3 above. I also loved B films and pulp fiction and wanted to doff my cap in their direction. Q A minor point: but why were you so insistent in obtaining the Magritte paintings for the film? This was a difficult and expensive business! A I’d forgotten it was expensive. Was it? I was attempting to make a film that was surreal and sinister at the same time - as is Magritte’s work. It appears early in the film and tips a knowing wink to the audience. It was called “L’Assassin Menace” and is a jokey premonition of what’s to happen. The Three Michaels Q Was this company set up solely to make Pulp (or what became Pulp)? Were there any further plans to make other films? Were there differences in the way that the participants viewed the company? Would it have continued if Pulp had been more commercially successful? A (Answers in order) Yes. No. No. I doubt it.The Chilian Club Q Your script is a very loose adaptation of the original. What was your attitude to George Shipway’s novel?A My memory cells are pretty dead on this subject. I seem to remember enjoying its anarchistic attitude to the power and class structure in the UK. It was “Pulp” from the fascist’s point of view. The Law & Order brigade with the bit between their teeth. Does that make sense in the context pf the novel?Q What was its attraction for M K, another socialist? A Much the same as mine??? Q Did you collaborate directly in the re-writing with Benny Green and M K? A No. General Q You seem very wary of ‘South African adventures’ and turned down the opportunity to direct Gold. What created this scepticism/uneasiness? A I never, ever wanted to make action films. And still don’t I was also reluctant to work in SA. Michael Klinger as producer Q You praise MK for his faith in young directors and in finding directors with whom he wanted to work. What would you say were the other qualities that made him stand out as a producer or that made him stimulating to work for? A Enormous energy and charm. He also cleverly spread his portfolio from populist to (almost) art cinema. Q Was MK a good judge of scripts? A See above Q Did he comment perceptively on rushes and suggest retakes or alterations or did he leave that to the director? A In my experience he voiced his opinions but ultimately always left it to the director. Q Did he ‘interfere’?! Were there ‘creative differences’ in the making of Get Carter or Pulp? A None - although he and Caine suddenly asked if I could work in a “chase” sequence. I reminded them of “Bullit” - and heard no more of that nonsense. Q Did Klinger’s approach to production differ from his contemporaries? (e.g. Dino de Laurentiis). A They were very similar in many ways. You were dealing with one man - not a committee. And they both loved Polanski! Q What would you say was MK’s contribution to British cinema? A He broke the public school ethos of the industry and wasn’t ashamed to make commercial films that might be considered in bad taste. And he produced “Cul-de-sac”, “Repulsion”, “Get Carter” (consistently voted one of the most popular British films ever made) and “Pulp”. That’s not a bad list, is it? I’ll always be grateful to him. back |

||