Publications

Andrew Spicer, University of the West of England:

The Creative Producer - The Michael Klinger Papers;

• Paper Given

at the University of Stirling Conference, Archives and Auteurs - Filmmakers

and their Archives, 2-4 September 2009

Introduction

This paper is based on documents that were deposited at the University

of the West of England in 2007 by Michael Klinger’s son, Tony. The

Klinger Papers are an archive that consists

of approximately 200 suspension files and numerous screenplays concerning

21 projects on which Klinger worked as producer or executive producer

from the late 1960s to the mid-1980s. They are a very rich source of material,

not available elsewhere, including itemized breakdowns of production costs;

film grosses; copies of financial agreements with investors; distribution

sales and territorial rights; television broadcasting deals; negotiations

with authors and actors over rights and payments; company profit and loss

accounts and promotion and publicity material. Comprehensive material

exists for several films, including Gold

(1974), which I have chosen as a case study. I was awarded a two-year

AHRC Research Grant in July to catalogue and interpret these papers. The

essential elements are: appointment of a full-time Research Assistant

(RA) who will work under my supervision to catalogue the Papers; place

selected documents online; conduct interviews with me of several creative

personnel who worked closely with Klinger; co-author articles and a monograph

on Klinger; organise a mid-point symposium that will debate the role of

the producer in British cinema. This last element forms part of a wider

project, which includes my work on Sydney Box

and the monograph published in Manchester University Press’s ‘British

Film Makers’ series, whose (modest!) aim

is to re-write British film history from the perspective of the ‘producer-artist’,

a formulation I’ll come back to in conclusion. The project will

commence in January after the RA has been appointed.

The Producer

Although Michael Klinger was the most successful independent producer

in the 1970s, he has become one of the legions of the lost in British

cinema. This occlusion, is symptomatic of the neglect of the producer’s

role within British cinema studies (and within Film Studies in general

- see Spicer, 2004), which, in Alexander Walker’s

deft formulation, ‘has to be resisted if films are to make sense

as an industry that can sometimes create art’ (Walker, 1986, p.

17). The producer is conventionally characterised as conservative, philistine

and anti-creative, as summarised by Ben Hecht’s

outburst: ‘The producer is a sort of bank guard. His objective is

to see that nothing is put on the screen that people are going to dislike.

This means practically 99 per cent of literature, thinking, probings of

all problems.’ (Quoted in Bernstein, 2000, p. 394). In contradistinction

to other creative personnel in the film industry - actors, set designers,

screenwriters, directors, cinematographers - the producer does not possess

a set of specific craft skills but rather what Leo Rosten defines as ‘the

ability to recognize ability, the knack of assigning the right creative

persons to the right creative spots. He should have knowledge of audience

tastes, a story sense, a businessman’s approach to costs and the

mechanics of picture making. He should be able to manage, placate, and

drive a variety of gifted, impulsive, and egocentric people’ (Rosten,

1941, pp. 238-39). Above all - and this, I suggest is his or her real

importance for analysis - the producer is involved in the whole production

process, as Michael Balcon characterizes the role: ‘[t]he one person

who can apprehend a film as an entity and be able to judge its progress

and development from the point of view of the audience who will eventually

view it’; a mediator between commerce and creativity, having ‘a

dual capacity as the creative man and the trustee of the moneybags’

(Balcon, 1945, p. 5). However, this role as mediator and anticipator of

audience taste does not have to be conservative, as Sydney Box argued:

‘A film producer has two responsibilities: to the public and to

his backers. If he is an imaginative and courageous producer, the two

may coincide. The ideal producer, it seems to me, must always look ahead

and try not merely to acquiesce in box-office trends but to lead public

opinion and gauge future audience requirements’ (Box, 1948).

With these general formulations in mind, I’d like to review Klinger’s

career briefly before turning to my case study to exemplify and concretise

some of the key issues.

Klinger’s Career

Rotund, cigar-chomping and ebullient - Sheridan

Morley described him as resembling “nothing

so much as a flamboyant character actor doing impressions of Louis B.

Meyer” (1)

- Michael Klinger might seem a caricature of the producer, but this image

belied a quicksilver intelligence, photographic memory and a cultivated

mind.

Born in 1920, the son of Polish Jewish immigrants who had settled in London’s

East End, Klinger’s entry into the film industry came via his ownership

of two Soho strip clubs, the Nell Gwynn

and the Gargoyle - that

were used for promotional events such as the Miss Cinema competition and

by film impresarios such as James Carreras

- and through an alliance with a fellow Jewish East Ender Tony

Tenser, who worked for a film distribution company,

Miracle Films. In October 1960, they set up Compton Films which owned

the Compton Cinema Club

- that showed, to anyone over twenty-one, nudist and other uncertificated,

often foreign, films - and Compton Film Distributors

which started out with a modest slate of salacious imported films (e.g.

Tower of Lust) and a

series of imaginative publicity stunts. However, finding it difficult

to obtain sufficient films, Klinger and Tenser started making their own

low-budget films, beginning with Naked as Nature

Intended (November 1961) directed by George

Harrison Marks and starring his girlfriend Pamela

Green (Hamilton, 2005: 10-14).

On the strength of a modest success, Tenser and Klinger formed a new company,

Tekli, to make several

films - including The Yellow Teddybears

(1963) and The Pleasure Girls

(1965) - that combined salaciousness with an attempt at examining serious

sexual issues, an assortment of different genres - comedy, period horror

and sci-fi - and two ‘shockumentaries’ - London

in the Raw (1964) and Primitive

London (1965).

Klinger and Tenser were highly ambitious, but culturally divergent. Characteristically,

when Roman Polanski

arrived in London and approached the pair to obtain finance having failed

elsewhere, it was Klinger who had seen Knife in

the Water (1962) and therefore gave him the

opportunity, and the creative freedom, to make Repulsion

(1965) and the even more outré Cul-de-sac

(1966). Although Repulsion

in particular had been financially successful, and both films won awards

at the Berlin Film Festival that conferred welcome prestige on Tekli,

Tenser, always happier to stay with proven box-office material, sex films

and period horror, saw Polanski as at best a distraction and at worse

a liability. These differences led to the break-up of the partnership

in October 1966.

Klinger set up a new company, Avton Films

and continued to promote young, talented but unproven directors who were

capable of making fresh and challenging features: Peter

Collinson’s absurdist/surrealist thriller

The Penthouse (1967);

Alastair Reid’s

Baby Love (1968), another

film that focused on a sexually precocious young female, but with an ambitious

narrative style that included flashbacks and nightmare sequences; and

Mike Hodges’s

ambitious and brutal thriller Get Carter

(1971). Although Get Carter

is now routinely discussed as Hodges’ directorial triumph, it was

Klinger who had bought the rights to Ted Lewis’s

novel Jack’s Return Home

because he sensed its potential to imbue the British crime thriller with

the realism and violence of its American counterparts and who had succeeded

in raising the finance through MGM-British all before Hodges became involved.

Part of Klinger’s success was his ability to tap into various markets.

In the 1970s he continued to make low-budget sexploitation films with

the “Confessions of”

series (Window Cleaner/Pop Performer/Driving Instructor/Holiday

Camp, 1974-78) for which he acted as executive

producer and whose modest costs could be recouped (in fact they made substantial

profits) (2) even from a rapidly shrinking

domestic market and partly compensate for an industry that now lacked

a stable production base, was almost completely casualised, and where

there was a chronic lack of continuous production. Klinger continued to

produce more recherché and challenging crime thrillers, including

Reid’s neglected Something to Hide

(1972), Collinson’s Tomorrow Never Comes

(1978) and Claude Chabrol’s

Les liens de sang (Blood

Relatives, 1978). However, Klinger’s main

energies went into the production of big-budget action-adventure films

- Gold (1974) and Shout

at the Devil (1976) - aimed at the international

market.

Given the parlous state of the British film industry, such a strategy

may seem odd or even reckless. However, the selection of the action-adventure

film was based on Klinger’s estimation of public taste - particularly

the popularity of the Bond films - and his conviction, in the context

of a dwindling domestic market, that international productions that could

hope for worldwide sales were the route to survival for the British film

industry. Indeed, he repeatedly attacked the insularity, parochialism

and timorousness of the British film industry in the trade press (3).

Klinger also saw an opportunity, with the withdrawal of large companies

(notably Rank) from

production, for ambitious (and, one might add, courageous) independent

producers to fill a production vacuum. His problem was that he could no

longer rely, as he had done for Get Carter

and Pulp (1972), on American

finance. As Alexander Walker

has shown, it was largely American money that had sustained the British

film industry in the 1960s and the withdrawal of Hollywood studios from

the industry in the 1970s was swift, unceremonious and catastrophic. The

production history of both Klinger’s action-adventure films would

reward extended analysis - Shout

was ‘one of the biggest independently financed films in British

cinema history’(4) - but for brevity’s

sake I will focus on Gold,

a more manageable focus than Klinger’s negotiations with Wilbur

Smith outlined in my abstract, but it does encompass

that relationship.

Gold: genesis and production context

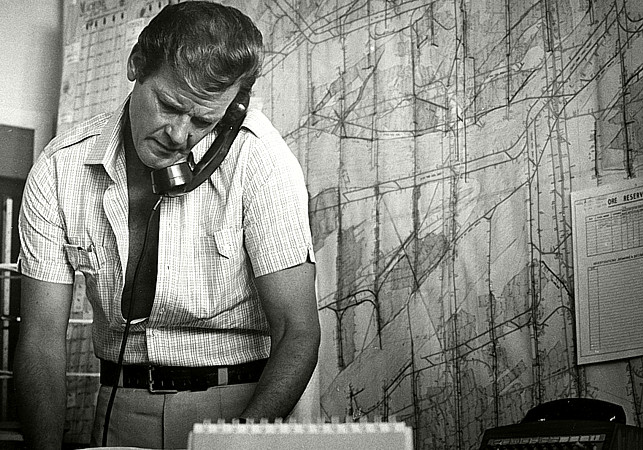

Klinger on location with Gold; the man to

his left is Peter Hunt, the director; courtesy of Tony Klinger

Klinger on location with Gold; the man to

his left is Peter Hunt, the director; courtesy of Tony Klinger

|

Gold is primarily

a disaster movie - a very successful genre in the 1970s - beginning and

ending with tense sequences depicting underground disasters in a South

African gold mine. Its hero, the mine’s General Manager Rod Slater

(Roger Moore), is

a contemporary, classless self-made man of action, whose virility derives

from his dangerous, exacting work and who shares with James Bond - particularly

through the casting of Moore who had just had starred in Live

and Let Die (1973) - a refined hedonism and

compulsive womanising.

Gold: Roger Moore as

Rod Slater; courtesy of Tony Klinger

Gold: Roger Moore as

Rod Slater; courtesy of Tony Klinger |

Slater falls in love with Terry Steyner (Susannah

York), the wife of his devious bisexual boss

Manfred Steyner (Bradford Dillman),

and the daughter of the mine owner Hurry Hirschfield (Ray

Milland). Unbeknown to Hirschfield, Steyner

works secretly for a shadowy international cartel (another Bondian ingredient)

led by Farrell (John Gielgud).

By masterminding an operation to tunnel through to a supposed new vein

of gold which will breach the sides of a vast underground lake, Slater

becomes an unwitting pawn in the cartel’s scheme to flood the whole

of South Africa’s central mining complex and thus force up the price

of gold. Lured away by Terry, another unwitting pawn, for an amorous weekend

at Hirschfield’s country retreat, Slater returns in the nick of

time and, together with the strongest black miner, Big King (Simon

Sabela) saves the mine from disaster. Sabela,

the ‘noble savage’ sacrificing his life to save the mine -

Alexander Walker saw

him as a latter-day Bosambo

from Sanders of the River

(1935) - is one of several residual elements of the Empire film in Gold

which repeatedly emphasises its exotic African location, including the

aerial shots of big game, and its perfunctory depiction of black tribal

dancing as an erotic spectacle for the white couple.

Gold: On-screen rugged

action: Big King (Simon Sabela) and Rod Slater (Roger Moore) try

to save the mine from flooding; courtesy of Tony Klinger

Gold: On-screen rugged

action: Big King (Simon Sabela) and Rod Slater (Roger Moore) try

to save the mine from flooding; courtesy of Tony Klinger |

Even with the action-adventure genre, Klinger was looking to produce a

series of films all derived from the bestselling novels of Wilbur

Smith. Klinger acquired the rights to Shout

at the Devil (1968) and Gold

Mine (1970), buying the latter even before publication,

judging that Smith’s brand of modern exotic action-adventure was

ideal cinematic material (5). He continued,

throughout the 1970s, to try to produce further films based on Smith’s

novels - succeeding with Shout

but failing with Eagle in the Sky

(1974), The Eye of the Tiger

(1975) and The Sunbird

(1972). In May 1970, while Get Carter

was still in production, Klinger was in active discussion with Smith over

a screenplay based on Gold Mine.(6)

Klinger was anxious to build on the cordial relationship he had developed

with Get Carter’s

financiers, MGM-British that had made the only Smith adaptation so far

- Dark of the Sun, released

in Britain as The Mercenaries

in 1968. MGM-British bought out Klinger’s option on Gold

Mine and engaged him as Gold’s

producer on similar terms to those he had negotiated for Get

Carter, thus affording him what he believed

would be a free hand in scripting and casting (7).

However, although Klinger engaged Smith to complete the adaptation of

his own novel, MGM-British brought in an experienced scriptwriter, Stanley

Price, to rewrite. A clearly exasperated Klinger

complained that he had ‘no knowledge whatsoever of your deal with

Stanley Price other than the overall figure I understand you have agreed

to pay him is £5,000 (8)’.

However, as part of the sudden withdrawal of American finance noted above,

MGM-British withdrew its interest in August 1973 (9).

Klinger purchased the rights to the Price screenplay and, as an accomplished

script editor, made some changes himself (10).

However, while he might have been free of interference, with MGM’s

withdrawal, Klinger lost his major source of production finance and also

his distribution guarantees in the all-important American market. To overcome

these problems took a huge effort, particularly as Klinger was unable

to raise the necessary finance in Britain, where the dearth of production

finance was acknowledged officially to be chronic (11).

Klinger himself had drawn attention to this on a number of occasions,

lamenting: ‘I try - and fail - to get British money every time …

It is the hardest place in the world to raise money for films. As a result,

we are letting ourselves be used as a workshop.(12)’

Emphasising that Gold

would be shot entirely on location, Klinger turned to South African businessmen

not used to backing films but whom he persuaded would see a handsome return

on their investment (13). Although this

deal ensured that Gold

could be made (for around $2,000,000, a figure quoted in several reviews),

it was always a precarious arrangement that generated considerable mutual

mistrust. In particular, there was a protracted wrangle over who was responsible

for paying the overages when the film went over budget as the mine-disaster

sequences proved to be more costly to shoot than was anticipated and involved

an expensive studio recreation at Pinewood. Klinger’s South African

financiers expected to see a return on their investment based on the original

estimates that they had agreed and not the final costs (14).

Because the scope and scale of Gold

was extraordinarily ambitious for an independent British producer, its

production required adroit budgeting, careful casting and strict overall

control. Convinced that Roger Moore

was ideal for the lead and could guarantee international sales, Klinger

had negotiated with Moore even before he attained superstardom as Bond.

As the lynchpin, Moore was offered a lucrative deal: a fee of $200,000

plus five per cent of Gold’s

gross (15). Although Klinger could use

Moore’s star power positively - to raise finance and persuade other

star names (John Gielgud,

Ray Milland and Susannah

York), to take prominent parts - it could also

work negatively. Klinger judged that the director of Duel

(1971), Steven Spielberg,

was ideal for an action picture, and another talented young film-maker

whom he wanted to promote. However, Moore was unwilling to entrust the

direction of a major film, at what he judged to be a critical point in

his career, to someone aged only 27 and vetoed Klinger’s choice

(16). Klinger then decided to opt for

the experienced Peter Hunt

who had edited several Bond films before directing On

Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969) and

assembled a crew of other Bond regulars along with his others he had already

worked with, including art director Alex Vetchinsky

and director of photography Ousama Rawi.

Klinger also hired the highly experienced composer Elmer

Bernstein to score the film and placed his own

son Tony in charge of the second unit direction.

Thus although Klinger may have been frustrated by not getting Spielberg,

he has assembled a talented crew, experienced in action-adventure film-making,

many of whom he knew well, and over whom he was able to exercise close

supervision. Klinger was a ‘hands-on’ producer, present throughout

the shooting in South Africa as well as the restaging of some of the underground

sequences at Pinewood. In particular, he arranged the viewing of the daily

rushes to check for quality. His presence became very necessary because

the craft union, the Association of Cinema and Television Technicians

(ACTT), disapproved of its members working in the apartheid state of South

Africa and threatened not to handle the film in post-production and discipline

the crew (Mitchell, 1997, p. 83). Klinger robustly defended his choice

of location as the only appropriate one and argued that he should be supported

for creating work in a time of crisis within the industry. He also appointed

a QC to act for the technicians once they returned to England (17).

Reluctantly, under pressure from some of its own members, the union agreed

not to hinder the production (18).

Gold - Distribution

In addition to struggling to raise production finance, Klinger had immense

difficulties as an independent in obtaining a distribution agreement,

crucial to Gold’s

financial viability. He first approached British

Lion in November 1973 as potential UK distributors,

describing Gold as a

‘British Quota [that] has Poseidon Adventure

possibilities’(19), a reference

to the most successful of the early disaster movies. British

Lion’s Chief Executive Michael

Deeley declined, arguing that the drastic reduction

in the British ‘cinema market’ coupled with rising costs for

releasing a picture meant that ‘there is only a limited chance of

making a profit out of a straight UK deal’(20).

Deeley’s response reveals much about the domestic market at this

point. The Rank Organisation

also declined, as did Nat Cohen

at Anglo-EMI, but a deal was struck with Hemdale,

a relatively new organisation, founded in 1968 by David

Hemmings and John

Daly. Although Hemmings had left the company

in 1970, Hemdale had

established itself as an up-and-coming production/distribution company

and was ambitious to increase its share of the market. Knowing the pressures

on independent producers, Hemdale

was able to drive a hard bargain, offering Klinger a guarantee of only

£100,000 from the UK market, not the £200,000 he had been

seeking (21).

Negotiating an American distribution deal was equally tortuous. Klinger

hired Irvin Shapiro

of Films Around the World Inc.

in order to tout Gold

around the Majors. Paramount

expressed an interest and its President, Frank

Yablans, commented somewhat equivocally: ‘the

characters tend to be two-dimensional and the story is not original’

but ‘the mine sequences could work out to be very exciting visually’(22).

In the end, Paramount

passed on Gold and

it was the lower-ranking Allied Artists

(AA) that finally offered to finance the film. Klinger, disappointed by

Shapiro’s failure to conclude a deal, had negotiated the arrangement

himself at Cannes.

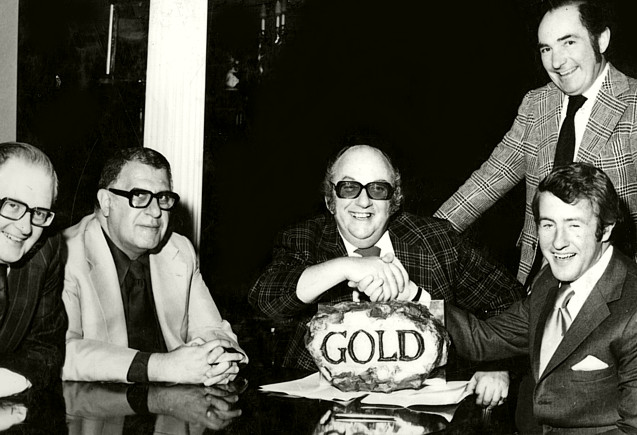

Gold and its makers

- left to right: John Hogarth (executive for Hemdale, distributors);

Paul Kijzer

Gold and its makers

- left to right: John Hogarth (executive for Hemdale, distributors);

Paul Kijzer

(sales agent for Avton Films); Michael Klinger (producer and head

of Avton Films); Peter Hunt, standing

(director); John Daly (co-founder of Hemdale and chief executive;

courtesy of Tony Klinger |

Conclusion

Much more could be said about Gold

- its exhibition, uneven critical reception, visual style, characterization

and narrative and its relationship with other British action-adventure

films - in all of which Klinger was intimately involved - but for brevity’s

sake I have limited myself to its production history and what this demonstrates

about the acute difficulties producers faced in the 1970s British film

industry, an era of acute audience decline and chronic fragmentation where

distributors ruled the roost and producers had to be nimble-footed to

survive let alone prosper. But I want to conclude by returning to the

importance of the producer’s role in general terms.

The particularities of the British film industry led John

Caughie to conclude: ‘The importance of

the producer-artist seems to be a specific feature of British cinema,

an effect of the need continually to start again in the organization of

independence (Caughie, 1986: 200).’ A ‘producer-artist’,

of course, is not the same entity as the auteur director whose artistry

may be recognized through a signature visual style or consistent thematic

preoccupations that can be elucidated through the detailed textual interpretation

of his or her films. As with most producers, Klinger’s oeuvre was

diverse and heterogeneous and would elude such an analysis. On the contrary,

understanding a producer’s art, as Vincent Porter argues, lies in

appreciating his or her ability to manipulate creatively the complex and

interlocking relationship between four key factors: an understanding of

public taste - of what subjects and genres could attract a broad audience;

the ability to obtain adequate production finance; the understanding of

who to use in the key creative roles and on what terms; and the effectiveness

of her or his overall control of the production process (Porter, 1983:

179-80). It is inescapably collaborative. The problem in appreciating

the ‘art’ of commercial feature film-making is that it is,

for the most part, invisible. The critical challenge is to render that

art visible by a detailed examination of the production process, understood

as encompassing not only the shooting of the film, but also its genesis

(as an idea, a script or even a hunch), and also its distribution, marketing

and exhibition. This requires considerable efforts of excavation, of archival

documentation, as well as analysis. However, without that effort, and

without appreciating the cultural and economic significance of the ‘producer-artist’,

we are not going to understand the 1970s, or the history of the British

film industry in general.

Appendix: Michael Klinger: Filmography

Naked as Nature Intended

(1961) pc. Markten/Compass, dis. Compton

That Kind of Girl (1963)

pc. Tekli, dis. Compton

The Yellow Teddybears

(1963) pc. Tekli, dis. Compton

London in the Raw (1964)

pc. Trotwood Productions, dis. Compton

Saturday Night Out (1964)

pc. Compton-Tekli, dis. Compton

The Black Torment (1964)

pc. Compton-Tekli, dis. Compton

Repulsion (1965) pc.

Tekli, dis. Compton

Primitive London (1965)

pc. Trotwood Productions, dis. Cinépix Film Properties

A Study in Terror (1965)

pc. Compton-Tekli, dis. Compton

The Pleasure Girls (1965)

pc. Tekli, dis. Compton

Cul-de-Sac (1966) pc.

Compton-Tekli, dis. Compton

Secrets of a Windmill Girl

(1966) pc. Searchlight-Markten, dis. Compton

The London Nobody Knows

(1967) pc. Norcon, dist. London Films

The Projected Man (1966)

pc. MLC, dis. Compton

The Penthouse (1967)

pc. Tahiti, dis. Paramount

La Mujer de mi padre/Muhair

(The Woman of My Father,

1968) pc. Compton Films International, dis. Haven International Pictures

(USA)

Baby Love (1968) pc.

Avton, dis. Avco Embassy

Barcelona Kill (1971)

pc. Avton, dis. Scotia (West Germany)

Get Carter (1971) pc.

MGM-British, dis. MGM-EMI

Pulp (1972) pc. Three

Michaels, dis. United Artists

Something to Hide (1972)

pc. Avton, dis. Avco Embassy

Rachel’s Man (1974)

pc. Longlade, dis. Allied Artists

Gold (1974) pc. Avton,

dis. Hemdale

Confessions of a Window Cleaner

(1974) pc. Swiftdown, dis. Columbia

Confessions of a Pop Performer

(1975) pc. Swiftdown, dis. Columbia

Confessions of a Driving Instructor

(1976) pc. Swiftdown, dis. Columbia

Shout at the Devil (1976)

pc. Tonav Productions, dis. Hemdale

Confessions from a Holiday Camp

(1977) pc. Swiftdown, dis. Columbia

Les liens de sang/Blood Relatives

(1978) pc. Classic Film Industries/ Cinevideo-Filmel, dis. Filmcorp Productions

Tomorrow Never Comes

(1978) pc. Classic Film Industries/Montreal Trust/Neffbourne, dis. Rank

Riding High (1981) pc.

Klinger Productions, dis. Enterprise Pictures

The Assassinator (1988),

pc. Ice International, dis. Cameo Classics

Notes:

‘Klinger the Independent’,

The Times, 20 December 1975.

The Cost of the four ‘Confessions of’

films was only £3,000,000 but the box-office gross was £22,000,000;

Klinger Papers (KP).

‘British Film Industry

Missing Boat by Emphasizing Insular Pix: Klinger’,

Variety, 17 May 1972; ‘Int’l Mkt.

Key To British Production’s Recovery: Klinger’,

Variety, 26 September 1973.

‘Ex-Engineer Klinger

Film Plans Run to 43 Mil. In Two Yrs.’,

Variety, 5 November 1975.

Klinger also acquired the rights to The

Sunbird (1972), Eagle

in the Sky (1974) and The

Eye of the Tiger (1975), but was not able to

produce any of these.

Letter to Michael Klinger from Wilbur Smith’s

solicitors, 13 May 1950; (KP).

Letter from Peter Stone at MGM-British to Klinger,

3 December 1970; KP.

Letter from Klinger to Stone, 6 April 1971; KP.

See the letter from Klinger’s solicitor Raffles

Edelman to Klinger, 7 August 1973; KP.

There is copy of a contract made with Chadwick

Hall for ‘rewriting and polishing’ the screenplay (KP: 17

September 1973), but I have been unable to unearth any information about

this writer.

See Cmnd 6372 - Future

of the British Film Industry: Report of the Prime Minister’s Working

Party [the Terry Report] (London: HMSO, 1976).

Quoted in Garth Pearce, ‘Klinger’s

crusade - put Britain back into its own big picture’,

Daily Express, 21 January 1977.

See the covering letter from Edelmann, 6 August

1974, and the three agreements with Tony Factor, Dennis Bieber (Soco Properties)

and the Ellerine Brothers; KP. The agreements were made with Metropic,

Klinger’s holding company based, for tax reasons, in Vaduz, Liechtenstein.

See the letter from London lawyers Fluxman and

Partners acting on behalf of the South African financiers, 1 April 1977;

KP. The matter dragged on and was the subject of legal proceedings, finally

being referred to arbitration in 1981.

Contract, dated 18 January 1974; KP.

Information obtained from an interview with Tony

Klinger, 11 June 2008.

Hugh Herbert, ‘Will

Gold bite the dust?’, Guardian, 24 November

1973.

Mitchell, 1997: 215.

Letter from Klinger to Michael Deeley at British

Lion, 23 November 1973; KP.

Letter from Deeley to Klinger, 3 December 1973;

KP.

Letter from John Hogarth at Hemdale to Klinger,

16 January 1974; KP.

Letter from Yablans to Shapiro, 6 November 1973;

KP.

References

Bernstein Matthew, Walter Wanger: Hollywood Independent

(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000).

Balcon, Michael, The Producer

(London: BFI Publishing, 1945).

Box, Sydney, ‘Sadism - It Will Only Bring

Us Disrepute’, Kinematograph Weekly, 27

May 1948, p. 18.

Caughie, John, ‘Broadcasting and cinema

1: converging histories’, in Charles Barr

(ed.), All Our Yesterdays: 90 Years of British

Cinema (London: BFI Publishing, 1986).

Hamilton, John, Beasts in the Cellar: The Exploitation

Career of Tony Tenser (Surrey: FAB Press, 2005).

Mitchell, John, Flickering Shadows: A Lifetime

in Films (Malvern Wells, Worcestershire: Harold

Martin & Redman, 1997).

Porter, Vincent, ‘The Context of Creativity:

Ealing Studios and Hammer Films’, in James

Curran and Vincent Porter (eds), British Cinema

History (London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1983).

Rosten, Leo, Hollywood: The Movie Colony, the

Movie Makers (New York: Harcourt Brace &

Co., 1941)

Spicer, Andrew, ‘The Production Line: Reflections

on the Role of the Film Producer in British Cinema’,

Journal of British Cinema and Television, 1:1 (2004), pp. 33-50.

Walker, Alexander, Hollywood, England: The British

Film Industry in the Sixties London: Harrap,

1986 [1974].

Top of page

back

|