Publications

Andrew Spicer, University of the West of England:

Why Study Producers?

• Paper given

by Andrew Spicer at the Dept. of Theatre, Film and Television Studies,

University of Aberystwyth, 2 November 2011

- Thanks to Jamie and Paul for the invitation.

As the AHRC project draws to its conclusion, this is a welcome opportunity

for me to reflect on the work undertaken and the understandings we - that

is the Research Assistant Anthony McKenna and I - seem to have reached.

So this paper tries to raise ideas and questions rather than overwhelm

you with scholarly knowledge of the minutiae of Klinger’s work.

For which: buy the book!

My premise is that the role of the producer has been misunderstood and

frequently stereotyped. A whole paper could be written about the perception

of the producer but this slide will have to suffice.

Image of the Producer

The caricature Philip French

invoked in his study of Hollywood moguls retains a strong hold in popular

consciousness, and, dare I say it, in film scholarship. Irwin

Shaw retains the cigar-chomping image but adds

the racist dimension. Hecht, as a writer, develops the philistine tag,

caricaturing the producer as conservative, timorous and inhibiting; a

restraining force on the dynamic creativity of filmmaking working on behalf

of the shadowy and venal world of commerce and the ‘bottom line’

which requires unchallenging formulaic entertainment. Like all stereotypes,

this caricature is built on a reductive understanding of traits which

Klinger certainly exemplified. He was Jewish, his parents moving to Soho

in 1913 from Poland. He was a showman, outgoing, ‘pushy’ in

that supercilious English sense of the parvenu, certainly loud, maybe

a bit vulgar. He smoked big cigars. However, and this is the major theme

of my paper, he was anything but a philistine.

This image partly explains why there are so few books about producers.

There are studies of the luminaries - from Hollywood: Sam

Goldwyn, David O.

Selznick, Irving Thalberg,

Hal Wallis, Darryl

F. Zanuck; in Britain: Alexander

Korda, Michael Balcon

and David Puttnam,

and, in Europe, Dino De Laurentis.

But these tend to be biographical rather than critical. There are populist

interviews/overviews: Tim Adler’s

The Producers: Money, Movies and Who Calls the

Shots and Helen De

Winter’s “What

I Really Want To Do Is Produce”: Top Producers Talk Money and Movies,

both 2006. There are a few scholarly studies notably Matthew

Bernstein, Walter Wanger:

Hollywood’s Independent (2000);

George F. Custen, 20th

Century’s Fox: Darryl F. Zanuck and the Culture of Hollywood (1998);

and my own monograph on Sydney Box

(2006), still the only study of a producer in MUP’s ‘British

Film Makers’ series. So: very little.

Why?

Critical Neglect

The first reason is the long shadow of the auteur theory and the historical

privileging of the director’s ‘vision’ as the central

creative force in filmmaking. For reasons of time, I don’t want

to justify that contention, though I’m happy to in the Q&A.

The second reason merits some pause: what do producers do? On a basic

level, as recognised within the film industry itself, a producer needs

to be distinguished from an associate or line producer (or production

manager) whose job is to control the logistics of an actual production.

Alvarado and Stewart in their study of Euston Films make a useful distinction

between those who have allocative rather than operational control, the

difference between those who decide who does what and those whose role

is to implement those strategic decisions. Another distinction is between

what Mervyn LeRoy

called the ‘creative producer’ and the ‘business administrator

producer’, the former dealing with the artistic aspects of a production

(including scripting, casting and direction) and the ones who are primarily

responsible for obtaining production finance and handling business matters,

sometimes referred to as executive producers. I’m going to return

to the issue of creativity at the end.

That’s a start, but really not that helpful because most producers

combine the two roles and many actually see that combination as the key

aspect of the role, which I’ll come back to.

The next point is another contention that I haven’t time to document.

I’ll just quote Richard Maltby

who argues in his essay in Contemporary Hollywood that as a discipline

Film Studies has been weakened by a disabling split between studies of

economic film history that have ‘largely avoided confronting the

movies as formal objects’ and practices of textual analysis that

have ignored production contexts (25-6). I think that’s true. Eric

Smoodin in ‘The

History of Film History’ argues that it

obscures an earlier tradition of film scholarship that ‘stressed

issues of industry and consumption’ until these were displaced by

the auteur-director and the decontextualised analysis of films from the

mid-1950s onwards. Scholars are now rediscovering earlier ethnographical/anthropological

studies of the ‘Hollywood colony’

by Leo Rosten (1941)

and Hortense Powdermaker

(1950) - as shown in the recent collection Production

Studies (2009) edited by Mayer, Banks and Caldwell

- who have much to say about industry workers and the role of the film

producer. John Thornton Caldwell’s

monograph Production Culture

(2008) has been influential, exploring the discourses of the media themselves,

the ways in which film and television workers construct their own cultural

and interpretative frameworks, and thus the need to analyse their own

self-representations and ‘cultural self-performances’ that

are often neither logical nor systematic (5, 18). Caldwell’s focus

encourages an attention to the multifaceted nature of production practices

and to their embedded nature within industry cultures, including networking.

So there are hopeful signs that the producer is back on the agenda.

My final general point is that this focus on production/the producer is

an reorientation, a different emphasis not a reinvention of the discipline.

It’s not part of a plot to end discussion of directors ... or films!

Hence my evocation of Alexander Walker’s

deft phrase: ‘an industry that can sometimes create art’,

rather than an art form that gets contaminated by commerce.

Contents

The other major premise of the project is that to understand what a producer

does we need evidence; not gossip, journalistic speculation, self-serving

interviews and general discussions about industry funding or cultural

policy. We need detailed empirical studies. And that’s partly why

it’s so difficult to talk about producers because you can’t

get this ‘evidence’, as I’m calling it, from the text,

from watching the film. You have to use - of course critically - the trade

press, oral history, autobiographies and memoirs, and archival documentation.

That was the basis of the Klinger project and its a real privilege and

quite rare. Without that documentation it’s very difficult to conduct

a study with confidence. But my wider point is that although the object

of study includes the final film, it is not delimited by that; it’s

not text-based in the conventional sense but the study of a process -

and I’m understanding production here to include everything from

conception through to marketing and exhibition. Both Box and Klinger,

like all producers, tried to make far more films than they actually succeeded

in realising and often the ‘ones that got away’ in Box’s

phrase are more revealing because they throw into sharp relief all the

difficulties that surround a production - problems of raising finance,

casting, distribution, censorship, audience appeal and so on.

I want to come back to the implications of studying producers at the end

so I’ll develop briefly why I think the producer’s role is

significant as well as complex and what kinds of qualities might make

a good producer.

The creative organiser

I’m returning to Rosten - the first analyst to cut through the myths

surrounding film production and to amass a wealth of empirical data, conceiving

Hollywood as a dynamic social and cultural entity that was geared to a

mass market but which needed to treat each film as an individual product.

Rosten was keenly aware of the different labour hierarchies within the

‘colony’ and that cultural production was firmly situated

within wider social and economic networks. He understood the key role

played by the producer in the organisation of both the tangible and intangible

elements in film production: attempting to control properties (studios,

sets, and equipment), finance and diverse, often volatile, artistic temperaments.

It’s a useful compendium and stresses the ability to deploy people

effectively. You use, creatively, what others’ possess.

Michael Balcon

But to be an effective producer, I think, means having an idea, a conception,

a vision if you like, of the whole shooting match which Balcon’s

formulation captures. Balcon stresses the need to combine commerce and

art, a ‘dual capacity’ that can understand and appreciate

both. The contemporary British producer Eric

Fellner argued that a producer needs ‘creative

insight to make the right choices’ and ‘business acumen to

set out the whole [project] properly’. In his autobiography In

the Arena, Charlton

Heston, who worked with many different producers,

considered that a ‘real producer’ was ‘a special combination,

neither bird nor beast (or maybe both). He must have sound creative instincts

about script, casting, design … about film. At the same time he

must have an iron-clad grasp of logistics, scheduling, marketing, and

costs … above all costs.’ This desired combination of apparently

contradictory talents allows producers to perform what Bourdieu, in ‘The

Field of Cultural Production’, sees as

an essentially intermediary role, mediating between the creative world

of writers, directors, stars and cinematographers and the world of finance

and business deals.

It is this combination of art and commerce that allows the producer, usually,

to take overall charge of a production. Michael

Relph, who had a longstanding relationship with

the director Basil Dearden

- I’m drawing here on the recent study by Alan

Burton and Tim O’Sullivan

- makes a useful distinction between the more circumscribed role of the

director - ‘the tactical commander in control of the army in the

field - the actors and technicians on the studio floor’) - and the

more capacious role of the producer whom he saw as ‘the strategical

commander in control of the conception as a whole’. Although, Relph

averred, it is the producer’s responsibility to ensure that the

director is ‘serviced with the money, personnel and equipment he

needs’, it is the producer who is in ‘strategical command

of the film from an artistic viewpoint’ because the director may

lose sense of the ‘artistic proportions of the film as a whole.

/ These will have been previously determined by the producer, director

and writer, and the producer must see that the director brings their joint

conception to the screen.’ For David Puttnam,

the producer’s overall control is essential because experience led

him to understand that the key personnel involved in a film’s production

may have divergent conceptions; thus the producer’s prime role is

to ensure ‘that we’re all making exactly the same movie’.

Once Puttnam was convinced of that shared vision, his role was ‘to

protect the director and give him everything he needs’.

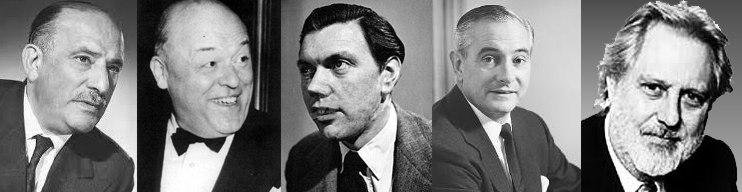

Producers Michael Balcon, Sydney Box, Michael

Relph, James Carreras and David Puttnam

Producers Michael Balcon, Sydney Box, Michael

Relph, James Carreras and David Puttnam |

Vincent Porter

I think the best overall formulation of the producer’s role is in

Vincent Porter’s

essay ‘The Context of Creativity’

which contrasts Michael Balcon

at Ealing with James Carreras

at Hammer. Porter argues that the producer’s skill lies his or her

ability to manipulate the complex and interlocking relationship between

four key factors: an understanding of public taste - of what subjects

and genres could attract a broad audience; the ability to obtain adequate

production finance; the understanding of who to use in the key creative

roles and on what terms; and the effectiveness of her or his overall control

of the production process.

Sydney Box

This ability to gauge public taste could be proactive as Sydney

Box suggested, whereby the producer becomes

a cultural leader and opinion-former.

What I’d add, something I’ve learned from my Research Associate

who wrote his PhD on Joseph E. Levine,

is the importance of showmanship, a quality recognised by Powdermaker,

who noted that this entailed a strong reliance on instinct and a confident

engagement with popular culture. At its extreme, this showmanship becomes

a producer’s defining quality: as was the case with Levine, with

whom Klinger worked on Baby Love

(1968). More recently, Jerry Bruckheimer

has successfully promoted himself as a brand that has a public presence

and market value. This showmanship need not always be outright self-promotion

but includes an ability to promote and hence sell the ‘package’.

Klinger was selling Linda Hayden,

the new starlet in Baby Love

- at 15 too young to see the picture she’s starring in. Nor should

it be necessarily associated with exploitation cinema or the lower end

of the marketplace, but can include promoting a film’s artistic

credibility and cultural respectability, its symbolic capital. In a subtle

study of Jeremy Thomas,

Christopher Meir identifies

Thomas’s principal skill as salesmanship, the promotion and marketing

of his films - which might include the reputation of the auteur director

working on the project - in order to sell them to potential financiers

and distributors and so be able to remain in business in the new global

marketplace. A producer’s showmanship often depends on building

a ‘reputation network’, creating ‘highly visible associations

which give stature and publicity potential by providing opportunities

for features and stories in the trade and popular press including announcing

new “discoveries”, highlighting awards and accolades and capitalising

on established or strongly emerging reputations. In this way the promotion

of the film becomes integral to the process of its production, with the

producer operating as what McKenna calls an ‘industrial tactician’.

I want to add two things before turning to Klinger. The first is that

although I have tried to identify some of the main qualities a producer

needs to possess, I’m not moving towards some skillset, indentikit,

normative conception of the role. Rosten, although he adumbrated that

handy conspectus, argued that if you really want to know what producers

do and how they do it: study individual producers. You can’t get

very far with generalisations. However, before we get to the case study,

there are important general contextual levels to which any case study

needs to refer.

Contexts

The first is the notion of independence. In the masthead to Klinger

News, Klinger always stressed the importance

being an independent rather than a studio producer, so without a direct

tie to a large corporation. De Laurentiis, for many years the leading

European independent, contrasted his time at Columbia where he was ‘half

employee, half slave’, with the ‘creative and entrepreneurial

freedom’ he enjoyed as an independent. However, while successful

independents such as De Laurentiis and Klinger had the resources to finance

preproduction and thus escape ‘interference’ at the formative

stage of a project, they have to obtain the bulk of production finance,

and a distribution deal, from others. A succinct if negative definition

of the compromised nature of a producer’s independence was provided

by Walter Wanger:

‘An independent producer is a man who is dependent on the exhibitors,

the studios and the banks.’ The independent producer’s dream

may be one of total autonomy but it is an impossible one given the huge

financial investment that making a feature film involves. Indeed, raising

finance and ensuring a distribution deal tend to dominate the lives of

independent producers, often displacing their wish to concentrate on production.

Independent production is also, historically, more associated with European

cinemas than Hollywood leading to a somewhat different conception of the

producer’s role in Europe, one which is more personalised and singularised,

revolving round particular individuals. Anne

Jackël argues in European Film Industries,

European producers characteristically insist that their role is not simply

to raise finance but is primarily creative. They are partly encouraged

to do this through the subsidy system employed by national governments

to support film production (quotas, levies, tax breaks, state funding,

subsidies and co-production agreements) which offer different kinds of

opportunities for the astute entrepreneur. However, although European

governments can influence production practices, and occasionally intervene

in exhibition, they are far less able to alter patterns of distribution

which are structured at an international level controlled by American

corporations.

In British Cinema Now

(1985) Nick Roddick

argued that British cinema has fallen disastrously between the two stools

of the Hollywood-style studio system and the European state-subsidised

model. It has, he asserts, ‘staggered from crisis to crisis (with

occasional very brief periods of health), because the British market is

not large enough to support a film industry built on the classic laissez-faire

model, and because government policy has never been sufficiently convinced

of either the economic or the cultural need for films to do anything which

might genuinely rectify the situation.’ This we need to situate

Klinger in this particular national cinema of Britain marooned uneasily

between Europe and America.

But in addition to situating the producer within broad social, cultural

and economic formations, we need to contextualise the role historically.

Janet Staiger has shown how the producer’s role shifts in American

cinema in The Classical Hollywood Cinema;

and Vincent Porter,

in ‘Making and Meaning: The Role of the

Producer in British Films’, which is coming

out in January in a special issue of the Journal of British Cinema and

Television on ‘The Producer’, demonstrates that the same is

true of British cinema. He shows that the role of the producer does not

emerge clearly until the mid-1920s and never attains the same stability

it enjoyed in Hollywood in the absence of a robust studio system and that

the real power lay with the exhibition circuits and American renters which

provided the finance. However, although the history of British cinema

is one of an almost uninterrupted series of crises as Roddick argues,

that very volatility has afforded, at certain moments, particularly when

the grip of established organisations within the film industry was weakened,

significant opportunities for the nimble-footed producers, which bring

us to the lad himself, Michael Klinger.

Michael Klinger: Overview

Early Career

Klinger was the product of multiple intersecting histories that created,

in Bourdieu’s terms, a particular habitus that disposed him to act

in particular ways. What qualities did Klinger bring to the role of the

producer? First, he looked the part. Cigar-smoking, rotund and ebullient,

Klinger ‘resembles nothing so much as a flamboyant character actor

doing impressions of Louis B. Meyer’, as Sheridan

Morley described him in 1975. This lineage from

the great tradition of Hollywood showmen is important - Peter

Noble emphasised a British pedigree: ‘Klinger

is an impresario on the lines of the late Alexander Korda on whom his

mantle appears to have fallen’– because Klinger was proud

to belong to that tradition. ‘One thing that’s missing in

this town today is showmanship. The oldtimers knew about showmanship -

how to bang the drum - and a lot of that’s gone now and more’s

the pity. We have to find something that triggers the public into wanting

to see the film.’ He was acutely conscious that in an era of increasing

corporate power, that tradition was in danger of being lost and the producer’s

role undermined: ‘Even the title has become diluted … where

not denigrated. And the producer’s “personal touch”

is largely missing in films of late.’

That belief in showmanship, the brashness, was partly attributable to

his origins as a second generation working-class West London Jewish socialist.

In his study of British Jewry, Geoffrey Alderman

observes that the Jewish workers’ outlook ‘differed fundamentally

from the British craft tradition; they saw themselves … as potentially

upwardly mobile, not as perpetual members of the proletariat’. As

in America, it was the characteristics of the film industry - ‘rapid

change, high-risk, the leverage attendant with the rewards’ - that

attracted bright working-class Jews. As his son Tony Klinger emphasised,

his father had no ambitions to be a director; he always wanted to be ‘the

guy who signed the cheques’. Klinger seized the opportunities offered

by the Soho sex industry of the 1960s, using his ownership of two Soho

strip clubs the Nell Gwynne

and the Gargoyle to

lever his way into the film industry. In October 1960 Klinger went into

partnership with fellow Jewish entrepreneur Tony

Tenser who worked for a distribution company

Miracle Films. Together

they set up Compton Films

which owned the Compton Cinema Club

- that showed, to anyone over twenty-one, nudist and other uncertificated,

often foreign, films - and a production-distribution company, Compton-Tekli,

making a series of low-budget ‘sexploitation’ films beginning

with Naked as Nature Intended (1961),

‘shockumentaries’: London in the Raw

(1964) and Primitive London

(1965) and more ambitious films - That Kind of

Girl (1963), The Yellow

Teddybears (1963) and The

Pleasure Girls (1965) - which combined salaciousness

with an attempt at examining serious sexual issues. They engage with a

rapidly changing British society as both fascinating and dangerous.

Klinger enjoyed showmanship but was neither vulgarian nor Philistine businessman.

When approached by Roman Polanski,

desperate to obtain production finance having failed elsewhere, Klinger

had seen Polanski’s first feature Knife in the Water (1962) at the

Cannes festival and was therefore willing to give him the opportunity,

and the creative freedom - if on a tight budget - to make Repulsion

(1965). Klinger appreciated Polanski as an

outré talent capable of making challenging films and also as a

means through which to increase his own and the company’s cultural

capital. He therefore promoted Repulsion

assiduously and its award at the Berlin Film Festival, represented a symbiosis

of directorial creativity and astute showmanship. By contrast, Tenser,

always happier to stay with proven box-office material, sex films and

period horror, saw Polanski as at best a distraction and at worse a liability.

These creative and cultural differences led to the break-up of the partnership

in October 1966.

Klinger’s espousal of talented but unproven directors continued

in his subsequent career as an individual producer. He produced the first

feature of Peter Collinson,

the challenging and controversial absurdist thriller The

Penthouse (1967), followed by Alastair

Reid’s Baby Love

(1968), another film that focused on a sexually precocious young female,

but with an ambitious narrative style including flashbacks and nightmare

sequences.

Such opportunities as the British cinema afforded in the 1960s became

rarer in the 1970s when conditions for aspiring producers were about as

difficult as could be imagined.

Klinger in the 1970s

I want to concentrate first on Klinger’s international ambitions

which may seems suicidal given these conditions. However, Klinger’s

conviction, in the context of a declining domestic market, was that international

productions which could hope for worldwide sales were the route to survival

for the British film industry. Indeed, he repeatedly attacked the insularity,

parochialism and timorousness of the British film industry in the trade

press. Klinger also saw an opportunity, with the withdrawal of large companies

(notably Rank) from

production, for ambitious independent producers to fill a production vacuum.

His selection of the action-adventure film was based on a shrewd estimation

of public taste - particularly the popularity of the Bond films - and

his two action-adventure films: Gold

(1974) and Shout at the Devil (1976)

were based on Wilbur Smith’s

middle-brow novels. However, if we look at the origins of Shout,

it does right back to 1967 when the novel appeared and before Smith’s

world-wide best-seller status thus showing Klinger’s astuteness

and ability to look ahead. When he came to make Gold

and Shout in the mid-1970s,

these were Hollywood style blockbusters, produced and marketed as such.

Gold

In these productions, Klinger became the fulcrum of a highly complex film-making

process involving lengthy negotiations with possible financiers - Klinger

used South African money in the absence of finance from American majors

- and reluctant distributors in Britain (Hemdale) and internationally

(Allied Artists) in the which the key agent was the producer himself allied

to commodity fiction (Smith’s increasing popularity) and the box-office

clout of his stars (in particular Roger Moore)

rather than the director.

Klinger’s ambitions, drive and internationalist orientation aligned

him with American producers - in the mid-1970s he was actually invited

to take over control of production at Columbia - and to a conception of

cinema as entertainment that needed to appeal to a broad public. On the

other hand, as Mike Hodges

recalled, Klinger was ‘very European … He had some instinct

to actually move towards art cinema in many ways, but still concentrate

on good storytelling.’ Tony Klinger

remembers his father’s admiration for ‘café society’,

enjoying the company of talented, cosmopolitan directors and the buzz

of film festivals. Thus he was prepared to make ‘unusual films’,

Polanski’s Cul-de-sac

(1966), Something to Hide

(1972) and the Biblical love story filmed in Israel, Rachel’s

Man (1976) as well as Chabrol’s

Les liens de sang (Blood

Relatives,1978).

But Klinger also remained true to his origins. He continued to make low-budget

sexploitation films with the “Confessions”

series (Window Cleaner/Pop Performer/Driving Instructor/Holiday

Camp, 1974-78) for which he acted as executive

producer. Their modest costs could be recouped (in fact they made substantial

profits) even from a rapidly shrinking domestic market and they were bankrolled

by Columbia which saw them as making a tidy sum.

The final category of 1970s films is the crime thrillers. Get

Carter, along with Repulsion,

is Klinger’s most famous film - well, not really, because nobody

associates Get Carter

with Klinger, but with Mike Hodges.

It’s Hodges who tours the circuits and appears at the retrospectives.

Of course, he’s alive and Klinger’s dead, but there is scant

mention of the producer in the fansites, 40th anniversary celebrations

etc. And yet it was Kligner who raised the finance - from MGM just before

it withdrew from British production - chose the novel while it was still

in galley proofs, sought out Michael Caine

as the star and then hired Hodges as an up-and-coming television director

whose thriller - Suspect

- Klinger admired. According to Caine, Klinger phoned him the evening

it was screened on LWT saying ‘we’ve found our man’.

I could say far more about Klinger - for instance he never succeeded in

raising any British finance for his films nor in accessing state subsidy

through the NFFC - but want now to draw out some of what I consider to

be the implications of the Klinger project.

Klinger’s importance

In summary, Klinger’s career can be characterized as the continuous

struggle between commerce (what would sell), cultural aspiration (making

innovative, challenging films that would showcase new and exciting creative

talent), and entrepreneurial ambition (to make big-budget films that would

rival American productions in the international marketplace). Klinger’s

independence afforded him control, not simply over the production process,

but over a film’s whole progress from conception to exhibition.

As shown, he was usually extensively involved in pre-production, not only

in securing a films’ finance, but in working with the writer (or

writer-director) on the screenplay. The scripts preserved in his papers

testify to his abilities in maintaining the ‘balance’ of a

script, in making judicious cuts, removing superfluous scenes and focusing

on the key elements of a screenplay that would make it possible to realise

the project adequately. Klinger was also very active in post-production,

not in editing, which he left to others, but in the promotion and marketing

of his films, frequently doing battle with distributors’ publicity

departments if he felt that they were either not energetic enough, or

unable, or unwilling, to give his films the care and attention, the sensitive

handling, he felt they deserved. On occasions - Polanski’s Cul-de-sac

or Hodges’ Pulp

(1972) - the conception of the project was that of the auteur writer-director,

but often the overall image, the dream, was usually Klinger’s. However,

this is not to try to impose an auteurist coherence over what is, by any

estimation, a heterogeneous range of films. Rather, what we argue is that

Klinger’s ‘genius’ lay in his ability to create, in

very difficult circumstances, a varied portfolio of work. His films straddled

modes of production - exploitation, middle-brow and art-house - that are

normally regarded as mutually exclusive, and, in the process, demonstrated

the porous boundaries between them. Like Levine, Klinger demonstrated

a ‘peculiar talent’ in catering for different levels of taste,

in packaging culture and capitalising on emerging trends.

We can say too, I hope, that because of his intimate involvement in production

processes, he offers, as studying a director would not or not as clearly,

a window onto important social and cultural issues: the British film industry

for sure, but also the Soho sex industry and the impact of the Jewish

entrepreneur on the British film and television industries.

What of the wider conceptual implications?

I hope the study will make a compelling case for Klinger’s importance

and inform wider histories as is already the case with Sue Harper’s

and Justin Smith’s forthcoming study of the 1970s The Boundaries

of Pleasure (2012) which refers to my work. I hope it will suggest that

we should re-examine the profound importance of the Jewish entrepreneur

- think of Alexander Korda,

Michael Balcon,

Sidney Bernstein,

Nat Cohen, Lew Grade,

the Ostrer Brothers,

Yoram Globus and

Menahen Golan (Cannon), James

and John Woolf and

Klinger’s erstwhile partner Tony Tenser

- in the British entertainment industry. I’m going to take that

forward in a forthcoming essay for a special issue of Studies

in European Cinema. Studying producers also

has implications as to how we write film history - as I argued in the

New Review of Film and Television Studies.

It will, I hope, encourage scholars and students to consider seriously

the critical potential of looking at producers.

Part of this significance is the challenge it poses to existing conceptions

of creativity, often, as noted, taken as the marker of the genuine producer

as opposed to the business administrator. De Laurentiis claimed he was

creative because he had the requisite ‘artistic feeling inside’

that cannot be taught or learned’, as opposed to his rival Carlo

Ponti who was a ‘gifted lawyer with a

nose for business, for deals’. Thus for producers, being creative

is an important form of cultural capital.

But in what ways is producer creative? Are they, as David

Hesmondhalgh suggests in his recent study Creative

Labour, ‘creative managers’, Bourdieu’s

cultural intermediaries, in a different category from ‘primary creative

personnel’ (writers, actors, directors, musicians and craft and

technical workers who include cinematographers, editors and sound engineers)?

Similarly, Martin Dale

in his book about the film industry The Movie

Game (1997) distinguishes between ‘true

creators’ (writers and directors) who are originators creating ex

nihilo, and the producer who is an ‘enabling mechanism’, practising

‘secondary creation’ by working on pre-existing material rather

than originating it. However, others see the process differently. Sam

Spiegel thought a producer should be able to

‘conceive a picture, to dream it up, to have the first concept of

what the film is going to be like when finished, before a word is written

or the director cast’. Hal Wallis

opined: ‘When you find a property, acquire it, work on it from the

beginning to the end and deliver the finished product as you conceived

it, then you’re producing. A producer, to be worthy of the name,

must be a creator.’

I suggest that this wrestling over primary and secondary creation comes

back to the issues around art and commerce. Art is creative, commerce

isn’t. But my work on producers suggest that this isn’t a

workable distinction. We can see creativity in another sense, as the ability,

so necessary for independent producers, in securing funds for a project

by manipulating markets, negotiating deals, pre-selling and all the other

elements of a complex financial package without which a film would not

be made. I argued in my study of Sydney Box

that actually his most creative work was in putting together the extraordinarily

complex and ambitious bids for British Lion and London Weekend Television

in 1964. I think showmanship, skilfully deployed, is a highly creative

activity and often how a film is promoted and positioned is crucial to

its eventual success. To perceive a producer’s role better, we need

to develop a new discourse that understands ‘creativity’ in

a more capacious and flexible way. I think that’s important because,

especially in the last 15 years or so, a tremendous premium has been placed

on creativity - ‘creative industries’, ‘creative cities’,

the ‘creative economy’, the ‘creative class’ -

by commentators, governments and institutional policy makers. Hence the

need for producers to assert their creativity as a form of recognition.

Particularly because, in contradistinction to other creative personnel

in the film industry - actors, set designers, screenwriters, directors,

cinematographers - the producer does not possess a set of specific craft

skills.

However, in another sense I think the debate over creativity is a chimera.

I suggest that rather than try to define creativity in any absolute sense,

we should understand it as context dependent and that the crucial issue

is the struggle for creative control and, how that is exercised in the

production process. Really, this is what the forthcoming book on Klinger

is all about as we attempt to make sense of his career. And that context

is not simply within the specifics of any production, but, as I tried

to suggest in relation to Klinger, its relationship to wider economic

and cultural forces. John Caughie

identifies the ‘desire for independence’ as formative in the

development of British cinema. In the absence of stable production conditions,

he argues, there was a imperative need for that independence to be organised,

hence protected and safeguarded. He suggests that the history of British

cinema should be conceived as the history of its producers: ‘Outside

of a studio system or a national corporation, art is too precarious a

business to be left to artists: it needs organisers. The importance of

the producer-artists seems to be a specific feature of British cinema,

an effect of the need continually to start again in the organisation of

independence.’ (in Barr: 200) One could qualify that statement -

as indicated it is a characteristic of several European cinemas rather

than simply Britain - but nevertheless, Caughie provides a very productive

way of thinking about the producer’s role in an unstable film industry

such as Britain’s. The ‘producer-artist’ is not, of

course, the same entity as the auteur director whose artistry may be recognized

through a signature visual style or consistent thematic preoccupations

that can be elucidated through the detailed textual interpretation of

his or her films. Rather it can only be grasped through studying the production

process - from conception to exhibition.

Pedagogy

My final point is that this has important pedagogical implications abut

how we teach film and what the object of study is. As Eric

Smoodin notes in ‘The

History of Film History’, most film classes

are 3 hours in duration and wrapped around a film screening that invites

the film-as-text-for-interpretation approach. It trains film students

to think in that way. No wonder they love directors! The trouble with

locating and discussing a producer’s ‘art’, is that,

unlike the director’s that can be discussed using textual sources,

it is elusive because it is, for the most part, invisible. The critical

challenge, as I’ve suggested, is to render that art visible by providing

the resources to do that. However, as Ed Buscombe

argued in ‘Notes on Columbia Pictures Corporation’

published in Screen

36 years ago, many of the basic materials needed to facilitate this kind

of scholarship are not available. For currently active producers, these

materials may be acutely sensitive. I’m not saying this is a purely

archival issue. Students need to look at sources that take them beyond

the film text: to newspapers, the trade press, fan magazines, studio publications,

press books, industry records, government papers.

We’re trying to address this issue through placing as much material

as we can from the Klinger archive online and the Sally

Potter archive - SP-ARK - indicates a way forward:

the attempt to make a visually imaginative, interactive website that students

could enjoy using. When I first conceived the project it was all about

articles and the book, but now I see that perhaps it’s the website

that’s ultimately more significant and not the slightly apologetic

afterthought it was in the bid. Hence I’m going to apply for the

AHRC’s ‘Follow-On’ funding scheme to develop it and

to enable me - if I get it! - to consult with people within academia and

the industry about how we can take the study of producers forward. But

books too - I’ve placed a proposal with Continuum for an edited

collection: Beyond the Bottom Line: The Producer

and Screen Studies.

And that’s where I’d like to leave it today - to invite your

comments, suggestions and ideas as well as try to answer any questions

about Klinger and the role of the producer.

Thank you.

Top of page

back

|